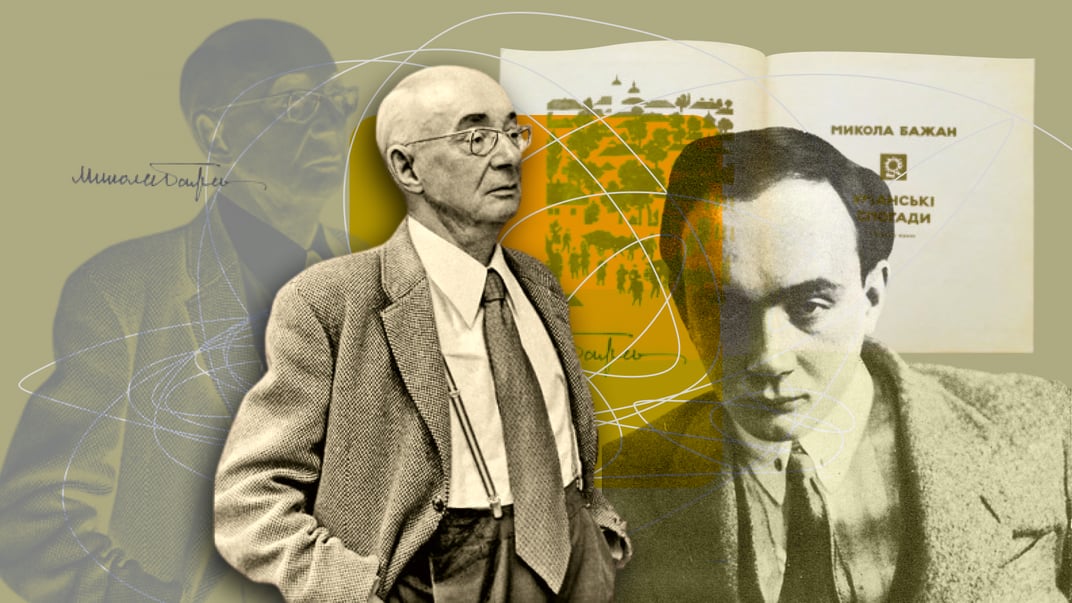

Mykola Bazhan. Stalin's order-bearer who retained his genius

I was at school when Mykola Bazhan was still a living classicist. The dull face of a party functionary looked at me from a textbook. It was very suitable for his position: member of the Communist Party of Ukraine Central Committee, member of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, deputy head of the Ukrainian government.

The teacher tried in vain to convince me that a man with such a face and such a record was a poet. Besides, his poems were not memorable: they could not be memorized during the break before class.

That's why my first question to Bazhan's only grandson, Oleksii, was this: “How did you feel when you had to learn your grandfather's poems at school?”

“Somehow, it was okay. Yesterday we studied Tychyna, today we studied Bazhan. What's so unusual about that? For example, they asked me to memorize two stanzas from his poem about Gastello, so I memorized these two stanzas,” says Oleksii.

With independence, Bazhan's works were removed from the school curriculum. It was easier than one might think: why did Omeljan Pritsak, the founder and first director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University, submit Mykola Bazhan's candidacy for the Nobel Prize in Literature to the Nobel Committee in 1970? Is it really for the poems of the poet from the school textbook? Or for the ones we never had the chance to read?

“Mykola Bazhan, as a poet, was incredibly unlucky with time,” says Ukrainian writer Stepan Protsiuk.

Yes, he was unlucky. Because the genius, to whom the secrets of the divine and human were revealed, was forced to glorify the Soviet government, its leaders, and the friendship of the Ukrainian and Russian peoples. It was like forcing Paganini to play the balalaika.

The Soviet government did not shoot Bazhan, like Semenko or Pluzhnyk. It Jesuitically emasculated his talent, turned him into an idol of the presidium, and held him tightly by the throat so that only censored notes would come out of him. This is how it killed the poet in Tychyna. But it did not succeed with Bazhan. The genius preserved himself.

From futurist rebellion to cooperation with the NKVD

1921. A seventeen-year-old boy in love with futurism comes from his native Uman to Kyiv to study at the then Cooperative Institute. His father was a lieutenant colonel in the tsarist army, an officer in the UPR army, and his mother was a graduate of a Kyiv gymnasium, a spiritual daughter of the Hromada, and an ardent supporter of the Ukrainian idea.

But if the Bolsheviks promise to radically modernize the peasant Ukraine, then he, Nick Bazhan, is for the Bolsheviks and cardinal revolutionary transformations. Studying to be a cooperator and a diplomat is a mistake. Bazhan drops out and, with Mykhail Semenko's blessing, begins to engage in journalism and write poetry. Bazhan's poems were successfully published in collections of pan-futurists.

He edited the first Ukrainian magazine about cinema and wrote screenplays. His screenplays were used in 7 films, 4 of which have survived to this day and are a treasure of the Dovzhenko Center.

In short, a powerful start in literature, a great and undeniable talent. He is gaining height and…

...In August 1929, the NKVD put the 25-year-old poet in a secret register as a representative of the “Ukrainian active community”. After all, he communicates with people involved in the case of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine (SVU).

Among the first denunciations of Bazhan was a statement by his younger brother's wife, Zhanna. The poet himself, his wife, and certain friends allegedly were “chauvinists and counterrevolutionary”.

Since then, the denunciations have multiplied. The poet was suspected of Ukrainian nationalism, sympathy for the Nazis, participation in anti-Soviet organizations, and being called a cosmopolitan Jew.

For 23 years, Bazhan was closely monitored by the Soviet secret services. He received Stalinist prizes, orders, and was a government official. But the case against him was not closed until October 1952!

Meanwhile, the trial of the Ukrainian intelligentsia in the SVU case took place, and Bazhan participated in collecting material aid for the families of the repressed. It is not known how he reacted to Khvylovy's suicide and the Holodomor. Bazhan kept his reflections to himself.

However, in September 1934, at the first congress of writers of the USSR in Moscow, he was finally broken through. NKVD agents quoted the poet's backstage conversations: “Moscow is alien to us, we have long been visitors to Western culture, we are Europeans.”

With fear in heart

Is it any wonder that in 1935 Bazhan was prosecuted as a member of the underground Ukrainian Military Organization?

By that time, many of the Ukrainian artists we now call the “Executed Renaissance” had been arrested. Mykola's friend and peer, the poet Marko Voronyi, was arrested.

“I think that the authorities were already planning to get Mykola to cooperate, so they allowed him to meet with Marko. During the visit, he realized what happens to intelligent people in prison. I think Bazhan was scared. And when the authorities offered him cooperation the following year, he agreed.

Obviously, he thought he could sneak through somehow. These were verbal agreements. As an agent, Bazhan had the pseudonym Petro Umanskyi. He had to write denunciations against Oleksandr Dovzhenko. But he wrote in such a way that his curators in the authorities called him insincere, and his denunciations were called runarounds,” says Alona Artiukh, a researcher at the Mykola Bazhan Museum-Apartment in Kyiv, PhD in Philology.

According to the researcher, Bazhan was not arrested either then or later because the authorities wanted to use his talent to their advantage.

Bazhan did not know that they wanted to tame and use him. He writes ideological propaganda and is deathly afraid of arrest. His younger brother Valentyn has already been arrested, and his sister Alla's fiancé, the satirist Yurii Vukhnal, is in prison. His father and sister fled to Crimea, fearing arrest. How can Mykola escape?

His apartment in Kyiv is on the first floor of the Rolit building. When a “black crow” arrives at night to pick up the residents of the building, Bazhan hears the stomping of the KGB officers on the stairs. And the poet's heart stops: what if they knock on his door?

“Bazhan felt that they were about to come for him. He packed his things just in case and... for more than a year he slept in his pants every night (!) because he did not want to look miserable in front of his executioners — to stand in his underwear and helplessly feel for glasses in the dark (he had poor eyesight since childhood),” recalled the writer Yurii Smolych.

In order not to go crazy with fear, Bazhan even ran away from home and spent the night at his mother's classmate's house.

“If you have a talent, don't go into government”

In 1937, Bazhan translated The Knight in the Panther's Skin to mark the 750th anniversary of the poem's creation. At that time, many writers rushed to translate the Georgian classical poem to earn Stalin's favor, but the leader remembered Mykola's translation. So when a group of Soviet writers were awarded in Moscow in January 1939, Stalin personally ordered that Bazhan be included in the list.

“An order bearer is a person who, under Stalin, was already part of the nomenclature pool, so to speak. Bazhan also took this path of a civil servant. It is not known what he told himself about this. He did not write diaries, and he did not even discuss such things in letters to his family,” says Alona Artiukh.

Bazhan's first state task was to organize an exhibition to mark the 125th anniversary of Taras Shevchenko's birth. More came next: in March 1939, the non-partisan Bazhan greeted the participants of the 18th Congress of the CPSU in Moscow on behalf of the people of Ukraine. The following year, the poet became a communist himself, and a year later he became a party organizer of the Writers' Union of Ukraine.

During the Second World War, Captain Bazhan was a frontline correspondent and editor of the newspaper For Soviet Ukraine.

“He wrote many patriotic poems and essays. It was the only moment in the history of the USSR when Ukrainians were allowed to write about events in the Ukrainian context. For Ukrainian writers, it was a moment of emotional outpouring of everything that had accumulated over the previous years — during the Holodomor and repressions. Everything that had accumulated against Moscow was released against the Germans,” says Alona Artiukh.

Bazhan knew very well what price Ukraine paid in this war. The country had to be rebuilt from the ashes. Isn't that why he agreed to become deputy head of the Ukrainian government? And he held this position from 1943 to 1949.

“From Bazhan's biography, I came to the conclusion that if God has given you a talent, you should not go into government,” says literary critic Vira Ahieieva.

Because the position obliges. It obliges him to become a co-author (together with Pavlo Tychyna) of the pro-Stalinist anthem of Ukraine. To stigmatize Maksym Rylsky and Yurii Yanovsky at a writers' plenum for “bourgeois nationalism”, to join the persecution of Dovzhenko for his screenplay Ukraine on Fire. To put his signature under the article “Against nationalist distortions in the modern science of Ukrainian history”. To demand that the West extradite Stepan Bandera to the USSR as a “war criminal” at a meeting of the UN General Assembly...

Later, in his memoirs about Yurii Yanovsky, Bazhan would publicly apologize to his friend: “It's not easy for me to write about this, but I also spoke in a way that I should not have. I have not and will not erase this from my memory, I will not throw off this burden.”

Probably, Bazhan perceived his other speeches against Ukrainian artists as an eternal burden.

“Bazhan held high positions, but he still had a reason to fear the authorities. The parents of his wife Nina were ethnic Germans and during the occupation of Kyiv they applied for a Volksdeutsche ID. They wanted to leave with the Germans, but they couldn't. Bazhan's father-in-law did time for this. So every day Mykola Platonovych could be accused of espionage, of having family ties to traitors. It was very threatening. That's why he played it safe and was very cautious in everything,” says Alona Artiukh.

Not a black and white story

Bazhan tried to use his official position and status to do something useful for Ukraine. Let's recall a few moments.

In 1943, together with Dovzhenko, they compiled a list of repressed Ukrainian figures whom they asked to release from prison. Bazhan did not know that the people on this list had been shot long ago. Only Ostap Vyshnia could be returned from the camps.

In July 1956, Bazhan raised the issue of rehabilitating repressed writers Hryhorii Epik, Ivan Kyrylenko, Oleksa Slisarenko, Mykola Kulish, Oleksa Vlyzko, Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, and many others before the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine.

Thanks to Bazhan, Ukraine received comprehensive publications on its history, literature, and art, including the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia.

“Bazhan was the editor-in-chief of the Ukrainian Soviet Encyclopedia (only Ukraine and Russia had their own encyclopedias in the USSR). He personally edited all the articles. Thanks to him, repressed artists are also mentioned in the URE. Even though they are criticized there, their names have returned to the cultural space,” notes Alona Artiukh.

Thanks to Bazhan, the world's first Encyclopedia of Cybernetics was created (he ensured that it was published in Ukrainian), and the six-volume History of Ukrainian Art and Shevchenko Dictionary were written and published. In 1962, largely due to Bazhan's efforts, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine adopted a resolution “On the Publication of the History of Towns and Villages of the Ukrainian SSR.”

“If Bazhan could help Ukraine and Ukrainians without endangering himself, and he did,” concludes Alona Artiukh.

Beloved women

During the most difficult periods, Bazhan's wife, Haina Kovalenko, was with him. She was a poet and actress who played in Kurbas's Berezol theater and recited her poems at poetry evenings of the Panfuturist Association.

Two years after their marriage, in 1929, the couple had a daughter. Haina left the stage and wrote children's fairy tales and poems, translated Russian, Georgian, Polish, and even Japanese poets into Ukrainian. For many years she worked as a literary editor and translator at Ukrainfilm. She was outgoing, feisty, and temperamental. But this was not enough.

In 1938, Mykola met his old Kharkiv acquaintance Nina Lauer in Kyiv. She had graduated from medical school and had just become a candidate of medical sciences. Not long before her meeting with Bazhan, she lost her unborn child and learned from doctors that she would never be able to become a mother again. Her relationship with Mykola brought her back to life.

At first, only their closest friend, the writer Yurii Yanovskyi, knew about their secret walks in Kyiv parks.

But already in November 1938, an NKVD agent with the pseudonym Arrow recounts in his report Bazhan's lamentations about his desire to divorce Haina: “he says that he ‘cannot break the connection with a woman with whom he is bound not only by his past love, but also by the strong deep feelings of these years — fear.’ That they ‘did not sleep together for so many years, waiting for his arrest’, ‘lived the horror of these years together and experienced every new misfortune together’”.

Nevertheless, the Order of Lenin, which Bazhan received in 1939, was a kind of indulgence from the Soviet authorities. So the fear he had experienced with Haina receded a bit. Bazhan decided to get a divorce.

He got a five-room apartment in the Rolit house. Three of the rooms were occupied by Mykola's parents and Haina and Maiia, and Bazhan gave the other two to Yanovskyi. He and Nina moved into Yurko's two-room apartment.

However, he did not disown his ex-wife and daughter, and constantly helped them financially. “I didn't grow up without a father,” says Maiia Mykolaivna.

For five years, Bazhan lived with Nina “on faith”, and they were officially married only in 1944.

“Perhaps it was the fact that Haina was of proletarian origin, and for her culture was associated with bohemianism. Nina, like Bazhan, was brought up in an intelligent family, she knew a lot about music, painting, antiques, and everything that was dear to Bazhan. His love for Nina did not fade over the years. This is evidenced by the poet's letters to his wife, of which more than one and a half hundred have survived. He calls her his love, his girl in his letters, even when they were both over 70,” says Alona Artiukh.

Here are a few lines from these letters: “Let's take care of each other even more. Nothing has faded, nothing has passed, everything is with us: I am proud of you, of our love, because it is a pledge, a sign of the best that is in me and in you.”

“My grandfather called his wife Ninka, and she called him Mykola. He dedicated poems to her. Nina Volodymyrivna took very good care of him. They were a very good couple, it was clear that they loved each other,” says Oleksii.

Bazhan without a tie

When Bazhan, a laureate of the Stalinist, Leninist, and State Prizes of the Ukrainian SSR, Hero of Socialist Labor, and holder of numerous orders, returned to his apartment on Tereshchenkivska Street after meetings, presidiums, and speeches, he would take off his robe of a statesman and party figure, change into a bathrobe (literally), and become a human being.

Bazhan was very fond of classical music, painting, and books. He collected blown glass, Kosiv ceramics, Mezhyhiriia faience, and majolica. He was fond of painting — he had paintings by Kateryna Bilokur, Ivan Trush, Vasyl Krychevskyi, Mykola Pymonenko, Mykhailo Derehus, Ilya Repin, and Vasyl Polienov. He bought many of these paintings, especially trophy paintings from Europe, at auctions.

“He was sincerely interested in all this. Bazhan was a man of high culture. He had a huge collection of records — Bach, Mozart, Handel, Tchaikovsky, Wagner, Sibelius, Shostakovich. He brought books on art history from abroad that were impossible to buy in the USSR. He bought valuable Soviet publications through the Academy of Sciences. He had over 8 thousand volumes in his home library. And he read every one of these books. By the way, Bazhan had a speed-reading technique: he could read a book of 400-500 pages within two hours,” says Ms. Artiukh.

Oleksii says that his grandfather told him about books and music, but he never forced him to read or listen to anything, including his own works. Oleksii liked the various figurines on the secretary in his grandfather's office the most — he always wanted to play with them.

“My grandfather often gave me toys. But he never brought them to me from abroad — they were gifts from our stores,” Oleksii recalls.

The boy realized that his grandfather was an important person only when he was a teenager. But he was not really interested in “all this”. For him, his grandfather means walks in Shevchenko Park, stories about Mykyta the Fox, hugging him or running in for a minute after school, having lunch together, playing, and celebrating the New Year.

His grandfather was always busy, but at key moments in his grandson's life he found time for him. For example, he seriously discussed his choice of profession with him. He did not dissuade him from the physics department. He only asked him with sincere interest what he liked about physics.

“My grandfather did not put any pressure on me. He never pressured anyone in the family at all,” Oleksii recalls.

Bazhan impressed his grandson with his severity and restraint. He was stingy with emotions, even reserved. He spoke very carefully about the events of his life.

“I now realize that the life he had has taught him to be like this — not to say too much. And to do something useful whenever possible, even at the cost of compromise,” says Oleksii.

Afterword

“My grandfather died when I was 23 years old. I lived with my parents, had my school and university life, and saw my grandfather a few hours a week. And, to be honest, I didn't really think about what I should ask my grandfather. And when I had questions for him, I had no one to ask. Now I learn about my grandfather from the publications of literary critics,” Oleksii states.

Ironically, Bazhan's grave at the Baikove Cemetery in Kyiv is inscribed with words from his poem “A Man Stands in the Starry Kremlin,” dedicated to Stalin:

“To give to the Fatherland not the bits of souls, but the fullness of life or death!”

After the poet's death in 1983, Nina Volodymyrivna remained in her apartment on Tereshchenkivska Street to live out her days. According to her will, the Mykola Bazhan Memorial Museum was established in the apartment in 2004. All the things that were in the apartment became its exhibits.

In October 2022, the museum was damaged by Russian shelling. According to Alona Artiukh, its exposition was evacuated, but the building is still not open to visitors as repairs are underway.

- Share: