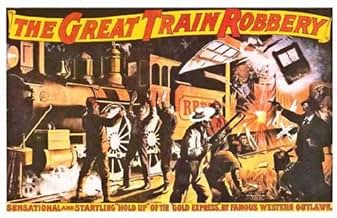

A group of bandits stage a brazen train hold-up, only to find a determined posse hot on their heels.A group of bandits stage a brazen train hold-up, only to find a determined posse hot on their heels.A group of bandits stage a brazen train hold-up, only to find a determined posse hot on their heels.

- Awards

- 1 win

Gilbert M. 'Broncho Billy' Anderson

- Bandit

- (uncredited)

- …

A.C. Abadie

- Sheriff

- (uncredited)

Justus D. Barnes

- Bandit Who Fires at Camera

- (uncredited)

Walter Cameron

- Sheriff

- (uncredited)

John Manus Dougherty Sr.

- Fourth Bandit

- (uncredited)

Donald Gallaher

- Little Boy

- (uncredited)

Shadrack E. Graham

- Child

- (uncredited)

Frank Hanaway

- Bandit

- (uncredited)

Adam Charles Hayman

- Bandit

- (uncredited)

Robert Milasch

- Trainman

- (uncredited)

- …

Marie Murray

- Dance-Hall Dancer

- (uncredited)

Frederick T. Scott

- Man

- (uncredited)

Mary Snow

- Little Girl

- (uncredited)

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaThe original camera negative still exists in excellent condition. The Library of Congress, who holds it, can still make new prints.

- GoofsWhen the telegraph operator revives with his hands tied behind his back, he uses one of his hands to help him stand up and then quickly puts the hand behind his back again.

- Alternate versionsThere is an Italian edition of this film on DVD, distributed by DNA srl, "CENTRO! (Straight Shooting, 1917) + IL CAVALLO D'ACCIAIO (The Iron Horse, 1924) + LA GRANDE RAPINA AL TRENO (The Great Train Robbery, 1903)" (3 Films on a single DVD), re-edited with the contribution of film historian Riccardo Cusin. This version is also available for streaming on some platforms.

- ConnectionsEdited into Hollywood: The Dream Factory (1972)

Featured review

Narrative Development: Structure

"The Great Train Robbery" was the most successful film to date, and its distribution preceded and eventually coincided with the spread of Nickelodeons across America. It didn't instantly create the Western genre; instead, it was part of and led to a spew of crime pictures--a genre begun in England. (G.M. "Billy Bronco" Anderson, who was somewhat of an assistant director on the film, would largely invent the movie Western a few years later after leaving the Edison Company, however.) Although the plot isn't very exciting today, the film remains a landmark in film history--mostly for its narrative structure. It's also notable how matter-of-fact, "realistic" and violent the film is for its time--being detailed and rather objective in its following of the details of the crime (what Neil Harris calls "an operational aesthetic"). The story film was already established by 1903 but was still in its infancy. Filmmakers were still experimenting with how to tell a narrative, and Porter was one of early film's greatest innovators, as well as an astute student of film.

Throughout his film-making career, Porter was strongly influenced by contemporary British and French films, which he would have ready access to since the Edison Company regularly duped them. His "Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show" is a rip-off of Robert Paul's "The Countryman and the Cinematograph." "The Gay Shoe Clerk" is a revision of George Smith's "As Seen Through a Telescope." Porter also introduced intertitles to American cinema in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," having seen them in some of Smith's films. "Life of an American Fireman" reflects James Williamson's "Fire!" The temporal replay in that film was influenced by Georges Méliès's temporal replay of the Moon landing in "Le Voyage dans la lune." "Dream of a Rarebit Fiend" also owes plenty to Méliès.

"The Great Train Robbery" followed a recently created genre of crime and chase films begun in England. "The Daring Daylight Robbery" was especially of influence, as was, it is said by historians, a 1903 film called "The Robbery of the Mail Coach." "The Great Train Robbery" is also based on a play of the same title by Scott Marble. News of real train robberies also served as inspiration according to the Edison catalogue. Anyhow, with the exception of wholesale rip-offs, it's not discourageable that Porter learned from other films and adopted techniques and style from them for his own. He is worthy of history's praise for being such an avid student of film and one of the more active filmmakers of his time to develop film grammar.

Some film historians and critics say that Porter's work was uneven, that "The Grain Train Robbery" and perhaps one or two other films were a happenstance success, or fluke. Someone was bound to figure out the techniques of narrative as story films became more complex--confronting such problems as spatially separate actions and the continuity of action. I've seen a good share of Porter's work, however, and it's apparent that he was usually experimenting. He wasn't consistent like Méliès, which is good because his work becomes stale. Porter's previous experiments in editing resulted in this, his most accomplished story film and greatest success.

There are a few special effects in "The Great Train Robbery," as others have mentioned. It's nothing new: double-exposure matte work for the shot of the train outside the window and for the outside of the moving train's door, hand coloring, in addition to stopping the camera and splicing to replace an actor with what is obviously a mannequin. Most amazing about this picture (for its time) are its structure and the editing and camera techniques employed for its continuity. Panning and tilting wasn't new, but this movement of the camera in one scene to follow the action is exceptional for 1903. Likewise, Porter and others had already used the close-up. Porter employed an insert of a fire alarm in "Life of an American Fireman" and a privileged camera position for "The Gay Shoe Clerk." The shock value of the close-up in this film even serves form as its entirety is supposed to thrill.

Furthermore, the view from on top of the train is quite good. The transitioning between interior and exterior shots is fluent, and generally so is the continuation of action from scene to scene, with action exiting and entering scenes from appropriate directions. This is elementary film-making now, but in 1903, they were inventing it.

What I think is the most interesting part of "The Great Train Robbery," though, is its editing between the plot of the telegrapher and that of the robbers after their initial confrontation. After following the robbers for a while, the film cuts back to the "meanwhile" plot of the telegrapher. Initially, the barn dance scene doesn't appear to serve any narrative function--until the telegrapher enters to gather a posse. It's an interesting ordering of and transitioning between parallel actions. The plot isn't in temporal order, and it's a nice testament to Porter's innovation that a few modern viewers have been perplexed by how the posse catches up with the robbers so quickly.

It would take D.W. Griffith and others to build upon past work and their own in moving towards more entertaining and cinematic films, but the developments in narrative experimented with by pioneers like Porter paved the way.

(Note: This is one of four films that I've commented on because they're landmarks of early narrative development in film history. The others are "As Seen Through a Telescope," "Le Voyage dans la lune" and "Rescued by Rover.")

Throughout his film-making career, Porter was strongly influenced by contemporary British and French films, which he would have ready access to since the Edison Company regularly duped them. His "Uncle Josh at the Moving Picture Show" is a rip-off of Robert Paul's "The Countryman and the Cinematograph." "The Gay Shoe Clerk" is a revision of George Smith's "As Seen Through a Telescope." Porter also introduced intertitles to American cinema in "Uncle Tom's Cabin," having seen them in some of Smith's films. "Life of an American Fireman" reflects James Williamson's "Fire!" The temporal replay in that film was influenced by Georges Méliès's temporal replay of the Moon landing in "Le Voyage dans la lune." "Dream of a Rarebit Fiend" also owes plenty to Méliès.

"The Great Train Robbery" followed a recently created genre of crime and chase films begun in England. "The Daring Daylight Robbery" was especially of influence, as was, it is said by historians, a 1903 film called "The Robbery of the Mail Coach." "The Great Train Robbery" is also based on a play of the same title by Scott Marble. News of real train robberies also served as inspiration according to the Edison catalogue. Anyhow, with the exception of wholesale rip-offs, it's not discourageable that Porter learned from other films and adopted techniques and style from them for his own. He is worthy of history's praise for being such an avid student of film and one of the more active filmmakers of his time to develop film grammar.

Some film historians and critics say that Porter's work was uneven, that "The Grain Train Robbery" and perhaps one or two other films were a happenstance success, or fluke. Someone was bound to figure out the techniques of narrative as story films became more complex--confronting such problems as spatially separate actions and the continuity of action. I've seen a good share of Porter's work, however, and it's apparent that he was usually experimenting. He wasn't consistent like Méliès, which is good because his work becomes stale. Porter's previous experiments in editing resulted in this, his most accomplished story film and greatest success.

There are a few special effects in "The Great Train Robbery," as others have mentioned. It's nothing new: double-exposure matte work for the shot of the train outside the window and for the outside of the moving train's door, hand coloring, in addition to stopping the camera and splicing to replace an actor with what is obviously a mannequin. Most amazing about this picture (for its time) are its structure and the editing and camera techniques employed for its continuity. Panning and tilting wasn't new, but this movement of the camera in one scene to follow the action is exceptional for 1903. Likewise, Porter and others had already used the close-up. Porter employed an insert of a fire alarm in "Life of an American Fireman" and a privileged camera position for "The Gay Shoe Clerk." The shock value of the close-up in this film even serves form as its entirety is supposed to thrill.

Furthermore, the view from on top of the train is quite good. The transitioning between interior and exterior shots is fluent, and generally so is the continuation of action from scene to scene, with action exiting and entering scenes from appropriate directions. This is elementary film-making now, but in 1903, they were inventing it.

What I think is the most interesting part of "The Great Train Robbery," though, is its editing between the plot of the telegrapher and that of the robbers after their initial confrontation. After following the robbers for a while, the film cuts back to the "meanwhile" plot of the telegrapher. Initially, the barn dance scene doesn't appear to serve any narrative function--until the telegrapher enters to gather a posse. It's an interesting ordering of and transitioning between parallel actions. The plot isn't in temporal order, and it's a nice testament to Porter's innovation that a few modern viewers have been perplexed by how the posse catches up with the robbers so quickly.

It would take D.W. Griffith and others to build upon past work and their own in moving towards more entertaining and cinematic films, but the developments in narrative experimented with by pioneers like Porter paved the way.

(Note: This is one of four films that I've commented on because they're landmarks of early narrative development in film history. The others are "As Seen Through a Telescope," "Le Voyage dans la lune" and "Rescued by Rover.")

- Cineanalyst

- Aug 1, 2004

- Permalink

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- Велике пограбування потягу

- Filming locations

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Budget

- $150 (estimated)

- Runtime11 minutes

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 1.33 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content

Top Gap

By what name was The Great Train Robbery (1903) officially released in India in English?

Answer