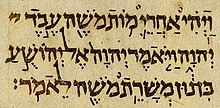

Aleppo Codex

The Aleppo Codex (Hebrew: כֶּתֶר אֲרַם צוֹבָא, romanized: Keṯer ʾĂrām-Ṣoḇāʾ, lit. 'Crown of Aleppo') is a medieval bound manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. The codex was written in the city of Tiberias in the tenth century CE (circa 920) under the rule of the Abbasid Caliphate,[1] and was endorsed for its accuracy by Maimonides. Together with the Leningrad Codex, it contains the Aaron ben Moses ben Asher Masoretic Text tradition.

The codex was kept for five centuries in the Central Synagogue of Aleppo, until the synagogue was torched during 1947 anti-Jewish riots in Aleppo.[2] The fate of the codex during the subsequent decade is unclear: when it resurfaced in Israel in 1958, roughly 40% of the manuscript—including the majority of the Torah section—was missing, and only two additional leaves have been recovered since then.[3] The original supposition that the missing pages were destroyed in the synagogue fire has increasingly been challenged, fueling speculation that they survive in private hands.[4][3]

The portion of the codex that is accounted for is housed in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum.[4]

Name

[edit]The codex's Hebrew name is כֶּתֶר אֲרָם צוֹבָא Keṯer ʾĂrām-Ṣoḇāʾ, translated as "Crown of Aleppo". Kether means "crown", and Aram-Ṣovaʾ (literally "outside Aram") was a not-yet-identified biblical city in what is now Syria whose name was applied from the 11th century onward by some Rabbinic sources and Syrian Jews to the area of Aleppo in Syria. Kether is a translation of Arabic tāj, originally Persian tāj; the codex was called al-Tāj by locals until the modern period. In Arabic, the term tāj was used mostly as a stock superlative title (Muslim caliphs did not wear crowns) and applied liberally to model codices. It lost this sense when translated into Hebrew as kether, which has only the literal sense of crown.[5]

History

[edit]Overview

[edit]The Karaite Jewish community of Jerusalem purchased the codex about a hundred years after it was made.[6][7] When the Crusaders conquered Jerusalem in 1099, the synagogue was plundered. The codex was held for a high ransom, which was paid with money from Egypt, leading to the codex being transferred there.[1] It was preserved by the Karaites, then at the Rabbanite synagogue in Old Cairo, where it was consulted by Maimonides, who described it as a text trusted by all Jewish scholars. It is rumoured that in 1375 one of Maimonides' descendants brought it to Mamluk-ruled Aleppo, leading to its present name.[1]

The Codex remained in Syria for nearly six hundred years. In 1947, rioters enraged by the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine burned down the synagogue where it was kept.[1] The Codex disappeared, then reemerged in 1958, when it was smuggled into Israel by Syrian Jew Murad Faham and presented to the president of the state, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. Sometime after arrival, it was found that parts of the codex had been lost. The Aleppo Codex was entrusted to the Ben-Zvi Institute and Hebrew University of Jerusalem. It is currently (2019) on display in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum.

Israel submitted the Aleppo Codex for inclusion in UNESCO's Memory of the World international register and was included in 2015.[8]

Ransom from Crusaders (1100)

[edit]The Karaite Jewish community of Jerusalem received the book from Israel ben Simha of Basra sometime between 1040 and 1050.[9] It was cared for by the brothers Hizkiyahu and Joshya, Karaite religious leaders who eventually moved to Fustat (today part of Old Cairo) in 1050. The codex, however, stayed in Jerusalem until the latter part of that century.[9] After the Siege of Jerusalem (1099) during the First Crusade, the Crusaders held the codex for ransom.[10][11] Letters in the Cairo Geniza describe the inhabitants of Ashkelon borrowing money from Egypt to "buy back two hundred and thirty Bible codices, a hundred other volumes, and eight Torah Scrolls" from the Crusaders[12] which may have included the codex.[13][11][10] A Judeo-Arabic inscription on the lost first page of the Codex described that the book was

Transferred according to the commandment to redeem captives, from the loot of the holy city of Jerusalem, may she be rebuilt and reestablished, to the Egyptian congregation, to the Jerusalemite synagogue, may [Jerusalem] be rebuilt and reestablished in the life of Israel. Blessed be he who preserves it and cursed be he who steals it or sells it or pawns it. It may never be sold or bought.[14]

In Aleppo

[edit]The Aleppo community guarded the Codex zealously for some 600 years: it was kept, together with three other Biblical manuscripts, in a special cupboard (later, an iron safe) in a basement chapel of the Central Synagogue of Aleppo, supposed to have been the Cave of Elijah. It was regarded as the community's most sacred possession: Those in trouble would pray before it, and oaths were taken by it. The community received queries from Jews worldwide, who asked that various textual details be checked, preserved in the responsa literature. It allowed for the reconstruction of information in the missing parts today. Most importantly, in the 1850s, Shalom Shachne Yellin sent his son-in-law, Moses Joshua Kimḥi, to Aleppo to copy information about the Codex; Kimḥi sat for weeks and copied thousands of details about the codex into the margins of a small handwritten Bible. The existence of this Bible was known to 20th-century scholars from the book ‘Ammudé Shesh by Shemuel Shelomo Boyarski, and then the actual Bible itself was discovered by Yosef Ofer in 1989.

However, the community limited outsiders' direct observation of the manuscript, especially by scholars in modern times. Paul E. Kahle, when revising the text of the Biblia Hebraica] in the 1920s, tried and failed to obtain a photographic copy. This forced him to use the Leningrad Codex] instead for the third edition, which appeared in 1937.

The only modern scholar allowed to compare it with a standard printed Hebrew Bible and take notes on the differences was Umberto Cassuto, who examined it in 1943.[15] This secrecy made it impossible to confirm the authenticity of the Codex, and indeed Cassuto doubted that it was Maimonides' codex, though he agreed that it was tenth century.

Loss of pages (1947–1958)

[edit]

During the 1947 Anti-Jewish riots in Aleppo, the community's ancient synagogue was burned. Later, while the Codex was in Israel, it was found that no more than 294 of the original (estimated) 487 pages survived.[2][17]

The missing leaves are a subject of fierce controversy. Initially, it was thought they were destroyed by fire, but scholarly analysis has shown no evidence of fire having reached the codex itself (the dark marks on the pages are due to fungus).[2] Some scholars instead accuse Jewish community members of having torn off the missing leaves and kept them privately hidden. Two missing portions of the manuscript—a single complete leaf from the Book of Chronicles and a fragment of a page from the Book of Exodus—were turned up from such sources in the 1980s, leaving open the possibility that even more may have survived the riots in 1947.[18][3] In particular, the 2012 book The Aleppo Codex by Matti Friedman calls attention to the fact that eyewitnesses in Aleppo who saw the Codex shortly after the fire consistently reported that it was complete or nearly complete, and then there is no account of it for more than a decade, until after it arrived in Israel and was put, in 1958, in the Ben-Zvi Institute, at which point it was as currently described; his book suggests several possibilities for the loss of the pages including theft in Israel.[19]

Documentary filmmaker Avi Dabach, great-grandson of Hacham Ezra Dabach (one of the last caretakers of the Codex when it was still in Syria), announced in December 2015 an upcoming film tracing the history of the Codex and possibly determining the fate of the missing pages.[20] The film, titled The Lost Crown, was released in 2018.[21]

In Israel

[edit]In January 1958, the Aleppo Codex was smuggled out of Syria and sent to Jerusalem to be placed in the care of the chief rabbi of the Aleppo Jews.[4] It was given first to Shlomo Zalman Shragai of the Jewish Agency, who later testified that the Codex was complete or nearly so at the time.[4] Later that year, it was given to the Ben-Zvi Institute.[4] Still during 1958, the Jewish community of Aleppo sued the Ben-Zvi Institute for the return of the Codex. The court ruled against them and suppressed the publication of the proceedings.[4]

In the late 1980s, the codex was placed in the Shrine of the Book at the Israel Museum.[3] This finally gave scholars a chance to examine it and consider the claims that it is indeed the manuscript referred to by Maimonides. The work of Moshe Goshen-Gottstein on the few surviving pages of the Torah seems to have confirmed these claims beyond reasonable doubt. Goshen-Gottstein suggested in the introduction to his facsimile reprint of the codex that not only was it the oldest known Masoretic Text (𝕸) in a single volume, but it was the first time that one or two people had produced a complete Tanakh as a unified entity in a consistent style.

During the Gulf War, and again during the Israel–Hamas war, the scrolls were placed in secure storage as part of the Israel Museum's emergency protocol.[22]

Reconstruction attempts

[edit]Later, after the university denied him access to the codex, Mordechai Breuer began his reconstruction of the Masoretic text based on other well-known ancient manuscripts. His results matched the Aleppo Codex almost precisely. Breuer's version is used authoritatively to reconstruct the missing portions of the Aleppo Codex. The Jerusalem Crown (Hebrew: כתר ירושלים, romanized: Keter Yerushalayim, lit. 'Jerusalem Crown'), printed in Jerusalem in 2000, is a modern version of the Tanakh based on the Aleppo Codex and the work of Breuer: It uses a newly designed typeface based on the calligraphy of the Codex and is based on its page layout.[23]

Superstitions

[edit]Among the Jewish community of Aleppo and their descendants in the post-1947 diaspora, the belief always was that the Codex holds great magical power and that the smallest piece of it can ensure its owner's good health and well-being.[3] Historically, it was believed that women allowed to look at it would become pregnant and that those in charge of the keys to the Codex vault were blessed.[3] On the other hand, history left every quire with the inscription "Sanctified to God, not to be sold or bought," and the first leaf once included a common warning for medieval Hebrew manuscripts,[24] "Cursed be he who steals it, and cursed be he who sells it."[14]

Authoritative text

[edit]The consonants in the codex were copied by the scribe Shlomo ben Buya'a in Palestine circa 920. The text was then verified, vocalized, and provided with Masoretic notes by Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, the last and most prominent member of the ben Asher dynasty of grammarians from Tiberias, rivals to the ben Naphtali school. The tradition of ben Asher has become the one accepted for the Hebrew Bible.[25] The ben Asher vocalization is late and in many respects artificial, compared to other traditions and tendencies reaching back closer to the period of spoken Biblical Hebrew.[26]

The Leningrad Codex, which dates to approximately the same time as the Aleppo codex, has been claimed by Paul E. Kahle to be a product of the ben Asher scriptorium. However, its colophon says only that it was corrected from manuscripts written by ben Asher; there is no evidence that ben Asher himself ever saw it. However, the same holds true for the Aleppo Codex, which was apparently not vocalized by ben Asher himself, although a later colophon, which was added to the manuscript after his death, attributes the vocalization to him.[27]

The community of Damascus possessed a counterpart of the Aleppo Codex, known as the Damascus Pentateuch in academic circles and as the "Damascus Keter", or "Crown of Damascus", in traditional Jewish circles. It was also written in Israel in the tenth century, and is now kept at the National Library of Israel as "ms. Heb 5702". It is available online here [1]. (This should not be confused with another Damascus Keter, of medieval Spanish origin.)

The Aleppo Codex was the manuscript used by Maimonides when he set down the exact rules for writing scrolls of the Torah, Hilkhot Sefer Torah "Laws of the Torah Scroll") in his Mishneh Torah.[11] This halachic ruling gave the Aleppo Codex the seal of supreme textual authority, albeit only concerning the type of space preceding sections (petuhot and setumot) and the manner of the writing of the songs in the Pentateuch.[27] "The codex which we used in these works is the codex known in Egypt, which includes 24 books, which was in Jerusalem," he wrote. David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra testifies to this being the same codex that was later transferred to Aleppo.[citation needed]

Physical description

[edit]The Codex, as it presents itself now in the Israel Museum where it is kept in a vault, consists of the 294 pages delivered by the Ben-Zvi Institute,[2][17] plus one full page and a section of a second one recovered subsequently.[3] The pages are preserved unbound and written on both sides.[3] Each page is parchment, 33 cm high by 26.5 cm wide (13 inches × 10.43 inches).[28] In particular, only the last few pages of the Torah are extant.[29] The ink was made of three types of gall, ground and mixed with black soot and iron sulfate.[3]

The manuscript has been restored by specialists of the Israel Museum, whose director declared that, given the Codex's history, it is "in remarkably excellent condition".[3] The purple markings on the edges of the pages were found to be mold rather than fire damage.[3]

Contents

[edit]When the Aleppo Codex was complete (until 1947), it followed the Tiberian textual tradition in the order of its books, similar to the Leningrad Codex, and which also matches the later tradition of Sephardi biblical manuscripts. The Torah and the Nevi'im appear in the same order found in most printed Hebrew Bibles, but the order for the books for Ketuvim differs markedly. In the Aleppo Codex, the order of the Ketuvim is Books of Chronicles, Psalms, Book of Job, Book of Proverbs, Book of Ruth, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Book of Lamentations, Book of Esther, Book of Daniel, and Book of Ezra and Book of Nehemiah.

The current text is missing all of the Pentateuch to the Book of Deuteronomy 28.17; II Kings 14.21–18.13; Book of Jeremiah 29.9–31.33; 32.2–4, 9–11, 21–24; Book of Amos 8.12–Book of Micah 5.1; So 3.20–Za 9.17; II Chronicles 26.19–35.7; Book of Psalms 15.1–25.2 (MT enumeration); Song of Songs 3.11 to the end; all of Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, and Ezra-Nehemiah.[26]

In 2016, the scholar Yosef Ofer published a newly recovered fragment of the Aleppo Codex with some portions of the Book of Exodus 8.[30]

Modern editions

[edit]Several complete or partial editions of the Tanakh based on the Aleppo Codex have been published over the past three decades in Israel, some of them under the academic auspices of Israeli universities. These editions incorporate reconstructions of the missing parts of the codex based on the methodology of Mordechai Breuer or similar systems, and by taking into account all available historical testimony about the contents of the codex.

Complete Tanakh: These are complete editions of the Tanakh, usually in one volume (but sometimes also sold in three volumes, and, as noted, in more). Apart from the last, they do not include the masoretic notes of the Aleppo Codex.

- Mossad HaRav Kook edition, Mordechai Breuer, ed. Torah (1977); Nebi'im (1979); Ketubim (1982); full Tanakh in one volume 1989. This was the first edition to include a reconstruction of the letters, vowels, and cantillation marks in the missing parts of the Aleppo codex. Mossad HaRav Kook also uses its Breuer text in other editions of the Bible it publishes, including its Da'at Mikrah commentary (complete in 30 volumes) and its Torat Hayim edition of Mikraot Gedolot, which thus far includes Torah (7 vols.), Psalms (3 vols.), Proverbs (2 vols.), and Five Megillot (3 vols.), as well as some non-Biblical texts such as the Haggadah.

- Horev publishers, Jerusalem, 1996–98. Mordechai Breuer, ed. This was the first edition to incorporate newly discovered information on the parashah divisions of the Aleppo Codex for Nebi'im and Ketubim. The text of the Horev Tanakh has been reprinted in several forms with various commentaries by the same publisher, including a Mikraot Gedolot on the Torah.[31]

- Jerusalem Crown: The Bible of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2000. Edited according to the method of Mordechai Breuer under the supervision of Yosef Ofer, with additional proofreading and refinements since the Horev edition.[31]

- Jerusalem Simanim Institute, Feldheim Publishers, 2004 (published in one-volume and three-volume editions).[31][32]

- Mikraot Gedolot Haketer, Bar-Ilan University (1992–present). A multi-volume critical edition of the Mikraot Gedolot, complete in 21 volumes: Genesis (2 vols.), Exodus (2 vols.), Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua & Judges (1 vol.), Samuel, Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Minor Prophets, Psalms (2 vols.), Proverbs, Job, Five Megillot (1 vol.), Daniel-Ezra-Nehemiah (1 vol.), Chronicles. Includes the masoretic notes of the Aleppo Codex and a new commentary on them. Differs from the Breuer reconstruction and presentation for some masoretic details.

Complete online Tanakh:

- Mechon Mamre provides an online edition of the Tanakh based upon the Aleppo Codex and related Tiberian manuscripts. Its reconstruction of the missing text is based on the methods of Mordechai Breuer. The text is offered in four formats: (a) Masoretic letter-text, (b) "full" letter-text (unrelated to masoretic spelling), (c) masoretic text with vowels (niqqud), and (d) masoretic text with vowels and cantillation signs. See external links below.

- "Miqra according to the Mesorah" is an experimental, digital version of the Tanakh based on the Aleppo Codex with full documentation of the editorial policy and its implementation (English-language abstract).

- Full text of the Keter https://www.mgketer.org

Partial editions:

- Hebrew University Bible Project (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel). Includes the masoretic notes of the Aleppo Codex.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Fragment of ancient parchment given to Jewish scholars". Archived from the original on 2009-07-07. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ^ a b c d Anshel Pfeffer (November 6, 2007). "Fragment of Ancient Parchment From Bible Given to Jerusalem Scholars".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ronen Bergman (July 25, 2012). "A High Holy Whodunit". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ^ a b c d e f Matti Friedman (June 30, 2014). "The Continuing Mysteries of the Aleppo Codex". Tablet. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014.

- ^ Stern, David (2019). "On the Term Keter as a Title for Bibles: A Speculation about its Origins". In Glick, Shmuel; Cohen, Evelyn M.; Piattelli, Angelo M. (eds.). Meḥevah le-Menaḥem: Studies in Honor of Menahem Hayyim Schmelzer. Jerusalem: Schocken. pp. 259–273.

- ^ M. Nehmad, Keter Aram Tzova, Aleppo 1933

- ^ Pfeffer, Anshel (6 November 2007). "Fragment of Ancient Parchment From Bible Given to Jerusalem Scholars". Haaretz.

- ^ "Aleppo Codex". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 2024-12-16.

- ^ a b Olszowy-Schlanger, Judith (1 January 1997). "The Karaite Nesīim". Karaite Marriage Contracts from the Cairo Geniza. Brill. p. 148. ISBN 978-90-04-49753-5.

- ^ a b Olszowy: pp. 54-55 and footnote #86

- ^ a b c The Vicissitudes of the Aleppo Codex Archived 2008-01-11 at the Wayback Machine – See 4.4 The Crusades and the Ransoming of Books. Retrieved on 2008–03–04.

- ^ Goitein, S.D. A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Vol. V: The Individual: Portrait of a Mediterranean Personality of the High Middle Ages as Reflected in the Cairo Geniza. University of California Press, 1988 (ISBN 0520056477), pg. 376

- ^ "A Synagogue in Old Cairo | Discarded History". Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ a b Meir, Nehmad (1933). "כתר ארם צובה". pp. 5–6.

- ^ "A Wandering Bible: The Aleppo Codex". The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Photo taken in 1910 by Joseph Segall and published in Travels through Northern Syria (London, 1910), p. 99. Reprinted and analyzed in Moshe H. Goshen-Gottstein, "A Recovered Part of the Aleppo Codex," Textus 5 (1966):53-59 (Plate I) Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Hayim Tawil & Bernard Schneider, Crown of Aleppo (Philadelphia, Jewish Publication Soc., 2010) page 110; there have been various reports and estimates of the original number of pages; Izhak Ben-Zvi, "The Codex of Ben Asher", Textus, vol. 1 (1960) page 2, reprinted in Sid Z. Leiman, ed., The Canon and Masorah of the Hebrew Bible, an Introductory Reader (NY, KTAV Publishing House, 1974) page 758 (estimating an original number of 380 pages).

- ^ Friedman, Matti (2012). The Aleppo Codex. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill.

- ^ Friedman (2012) ch. 24 and passim.

- ^ Maltz, Judy. "My Great-grandfather, the Man Who Held the Key to the Aleppo Codex". Haaretz. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ "הכתר האבוד • קטלוג הקולנוע הדוקומנטרי הישראלי". קטלוג הקולנוע הדוקומנטרי הישראלי (in Hebrew). Retrieved 2023-12-06.

- ^ Mishy Harman (2023-11-23). "Wartime Diaries: Hagit Maoz". Israel Story (Podcast). Public Radio Exchange. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

- ^ Glazer, Mordechai, ed., Companion Volume to Keter Yerushalam (2002, Jerusalem, N. Ben-Zvi Printing Enterprises).

- ^ See A. M. Haberman, History of the Hebrew Book [Hebrew] (1945), p. 20.

- ^ Zeev Ben-Hayyim (2007), "BEN-ASHER, AARON BEN MOSES", Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 3 (2nd ed.), Gale, pp. 319–321

- ^ a b P. W. Skehan (2003), "BIBLE (TEXTS)", New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Gale, pp. 355–362

- ^ a b Aron Dotan (2007), "MASORAH", Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 13 (2nd ed.), Gale, pp. 603–656

- ^ Hayim Tawil & Bernard Schneider, Crown of Aleppo (Philadelphia, Jewish Publication Soc., 2010) page 110; Izhak Ben-Zvi, "The Codex of Ben Asher", Textus, vol. 1 (1960) page 2, reprinted in Sid Z. Leiman, ed., The Canon and Masorah of the Hebrew Bible, an Introductory Reader (NY, Ktav Pubg. House, 1974) page 758.

- ^ The surviving text begins with the last word of Deuteronomy 28:17; Izhak Ben-Zvi, "The Codex of Ben Asher", Textus, vol. 1 (1960) page 2, reprinted in Sid Z. Leiman, ed., The Canon and Masorah of the Hebrew Bible, an Introductory Reader (NY, Ktav Pubg. House, 1974) page 758.

- ^ Ofer, Yosef (2016). "A Fragment of the Aleppo Codex (Exodus 8) that Reached Israel". Textus. 26 (1): 173–198. doi:10.1163/2589255X-02601009. ISSN 2589-255X.

- ^ a b c In this edition, the masoretic text and symbols were encoded and graphic layout was enabled by the computer program Taj, developed by Daniel Weissman.

- ^ "After consultation... with the greatest Torah scholars and grammarians, the biblical text in this edition was chosen to conform with the Aleppo Codex which as is well known was corrected by Ben-Asher... Where this manuscript is not extant we have relied on the Leningrad Codex... Similarly the open and closed sections that are missing in the Aleppo Codex have been completed according to the biblical list compiled by Rabbi Shalom Shachna Yelin that were published in the Jubilee volume for Rabbi Breuer... (translated from the Hebrew on p. 12 of the introduction).

External links and further reading

[edit]- The Aleppo Codex Website

- Mechon Mamre - Electronic text of the Hebrew Bible based largely on the Aleppo Codex.

- Wikimedia Commons - full online digital images in several files.

- Seforim Online Archived 2019-04-20 at the Wayback Machine - two online digital images, each in a single large file (the same images are found at the Wikimedia Commons in several smaller files)

- The History and Authority of the Aleppo Codex, by Yosef Ofer (pdf)

- Israel Museum shrine of the Book

- History of the Aleppo Codex

- "Rival Owners, Sacred Text" article in Wall Street Journal

- Segal, The Crown of Aleppo

- (in Hebrew) Copies of the Aleppo Codex Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine

- Dina Kraft, From Maimonides to Brooklyn: The mystery of the Aleppo Codex

- Matti Friedman, The Aleppo Codex: A True Story of Obsession, Faith, and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible, Algonquin Books (May 15, 2012), hardcover, 320 pages, ISBN 1616200405, ISBN 978-1616200404

- "Author Blog: Codex vs. Kindle By Matti Friedman" Archived 2013-06-17 at the Wayback Machine