Coproporphyrinogen III oxidase

| CPOX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | CPOX, CPO, CPX, HCP, coproporphyrinogen oxidase, COX, HARPO | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 612732; MGI: 104841; HomoloGene: 76; GeneCards: CPOX; OMA:CPOX - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EC number | 1.3.3.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coprogen oxidase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

coproporphyrinogen iii oxidase from leishmania major | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Coprogen oxidase | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF01218 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001260 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00783 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase, mitochondrial (abbreviated as CPOX) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the CPOX gene.[4][5][6] A genetic defect in the enzyme results in a reduced production of heme in animals. The medical condition associated with this enzyme defect is called hereditary coproporphyria.[7][8]

CPOX, the sixth enzyme of the haem biosynthetic pathway, converts coproporphyrinogen III to protoporphyrinogen IX through two sequential steps of oxidative decarboxylation.[9] The activity of the CPOX enzyme, located in the mitochondrial membrane, is measured in lymphocytes.[10]

Function

[edit]CPOX is an enzyme involved in the sixth step of porphyrin metabolism it catalyses the oxidative decarboxylation of coproporphyrinogen III to proto-porphyrinogen IX in the haem and chlorophyll biosynthetic pathways.[5][11] The protein is a homodimer containing two internally bound iron atoms per molecule of native protein.[12] The enzyme is active in the presence of molecular oxygen that acts as an electron acceptor. The enzyme is widely distributed having been found in a variety of eukaryotic and prokaryotic sources.

Structure

[edit]Gene

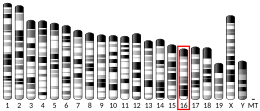

[edit]Human CPOX is a mitochondrial enzyme encoded by a 14 kb CPOX gene containing seven exons located on chromosome 3 at q11.2.[6]

Protein

[edit]CPOX is expressed as a 40 kDa precursor and contains an amino terminal mitochondrial targeting signal.[13] After proteolytic processing, the protein is present as a mature form of a homodimer with a molecular mass of 37 kDa.[14]

Clinical significance

[edit]Hereditary coproporphyria (HCP) and harderoporphyria are two phenotypically separate disorders that concern partial deficiency of CPOX. Neurovisceral symptomatology predominates in HCP. Additionally, it may be associated with abdominal pain and/or skin photosensitivity. Hyper-excretion of coproporphyrin III in urine and faeces has been recorded in biochemical tests.[15] HCP is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder, whereas harderoporphyria is a rare erythropoietic variant form of HCP and is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion. Clinically, it is characterized by neonatal haemolytic anaemia. Sometimes, the presence of skin lesions with marked faecal excretion of harderoporphyrin is also described in harderoporphyric patients.[16]

To date, over 50 CPOX mutations causing HCP have been described.[17] Most of these mutations result in substitution of amino acid residues within the structural framework of CPOX.[18] At least 32 of these mutations are considered to be disease-causing mutations.[19] In terms of the molecular basis of HCP and harderoporphyria, mutations of CPOX in patients with harderoporphyria were demonstrated in the region of exon 6, where mutations in those with HCP were also identified.[20] As only patients with mutation in this region (K404E) would develop harderoporphyria, this mutation led to diminishment of the second step of the decarboxylation reaction during the conversion of coproporphyrinogen to protoporphyrinogen, implying that the active site of the enzyme involved in the second step of decarboxylation is located in exon 6.[17]

Interactions

[edit]CPOX has been shown to interact with the atypical keto-isocoproporphyrin (KICP) in human subjects with mercury (Hg) exposure.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022742 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Lamoril J, Martasek P, Deybach JC, Da Silva V, Grandchamp B, Nordmann Y (February 1995). "A molecular defect in coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene causing harderoporphyria, a variant form of hereditary coproporphyria". Human Molecular Genetics. 4 (2): 275–8. doi:10.1093/hmg/4.2.275. PMID 7757079.

- ^ a b Kohno H, Furukawa T, Yoshinaga T, Tokunaga R, Taketani S (October 1993). "Coproporphyrinogen oxidase. Purification, molecular cloning, and induction of mRNA during erythroid differentiation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 268 (28): 21359–63. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(19)36931-5. PMID 8407975.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: CPOX coproporphyrinogen oxidase".

- ^ "Hereditary coproporphyria". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center. National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ "CPOX". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Sano S, Granick S (April 1961). "Mitochondrial coproporphyrinogen oxidase and protoporphyrin formation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 236 (4): 1173–80. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64262-0. PMID 13746277.

- ^ Guo R, Lim CK, Peters TJ (October 1988). "Accurate and specific HPLC assay of coproporphyrinogen III oxidase activity in human peripheral leucocytes". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 177 (3): 245–52. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(88)90069-1. PMID 3233772.

- ^ Madsen O, Sandal L, Sandal NN, Marcker KA (October 1993). "A soybean coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene is highly expressed in root nodules". Plant Molecular Biology. 23 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1007/BF00021417. PMID 8219054. S2CID 23011457.

- ^ Camadro JM, Chambon H, Jolles J, Labbe P (May 1986). "Purification and properties of coproporphyrinogen oxidase from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae". European Journal of Biochemistry. 156 (3): 579–87. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09617.x. PMID 3516695.

- ^ Martasek P, Camadro JM, Delfau-Larue MH, Dumas JB, Montagne JJ, de Verneuil H, Labbe P, Grandchamp B (April 1994). "Molecular cloning, sequencing, and functional expression of a cDNA encoding human coproporphyrinogen oxidase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (8): 3024–8. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.3024M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.8.3024. PMC 43507. PMID 8159699.

- ^ Martasek P, Nordmann Y, Grandchamp B (March 1994). "Homozygous hereditary coproporphyria caused by an arginine to tryptophane substitution in coproporphyrinogen oxidase and common intragenic polymorphisms". Human Molecular Genetics. 3 (3): 477–80. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.3.477. PMID 8012360.

- ^ Taketani S, Kohno H, Furukawa T, Yoshinaga T, Tokunaga R (January 1994). "Molecular cloning, sequencing and expression of cDNA encoding human coproporphyrinogen oxidase". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics. 1183 (3): 547–9. doi:10.1016/0005-2728(94)90083-3. PMID 8286403.

- ^ Kim DH, Hino R, Adachi Y, Kobori A, Taketani S (December 2013). "The enzyme engineering of mutant homodimer and heterodimer of coproporphyinogen oxidase contributes to new insight into hereditary coproporphyria and harderoporphyria". Journal of Biochemistry. 154 (6): 551–9. doi:10.1093/jb/mvt086. PMID 24078084.

- ^ a b Hasanoglu A, Balwani M, Kasapkara CS, Ezgü FS, Okur I, Tümer L, Cakmak A, Nazarenko I, Yu C, Clavero S, Bishop DF, Desnick RJ (February 2011). "Harderoporphyria due to homozygosity for coproporphyrinogen oxidase missense mutation H327R". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 34 (1): 225–31. doi:10.1007/s10545-010-9237-9. PMC 3091031. PMID 21103937.

- ^ Lee DS, Flachsová E, Bodnárová M, Demeler B, Martásek P, Raman CS (October 2005). "Structural basis of hereditary coproporphyria". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (40): 14232–7. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214232L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0506557102. PMC 1224704. PMID 16176984.

- ^ Šimčíková D, Heneberg P (December 2019). "Refinement of evolutionary medicine predictions based on clinical evidence for the manifestations of Mendelian diseases". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 18577. Bibcode:2019NatSR...918577S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-54976-4. PMC 6901466. PMID 31819097.

- ^ Schmitt C, Gouya L, Malonova E, Lamoril J, Camadro JM, Flamme M, Rose C, Lyoumi S, Da Silva V, Boileau C, Grandchamp B, Beaumont C, Deybach JC, Puy H (October 2005). "Mutations in human CPO gene predict clinical expression of either hepatic hereditary coproporphyria or erythropoietic harderoporphyria". Human Molecular Genetics. 14 (20): 3089–98. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi342. PMID 16159891.

- ^ Heyer NJ, Bittner AC, Echeverria D, Woods JS (February 2006). "A cascade analysis of the interaction of mercury and coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX) polymorphism on the heme biosynthetic pathway and porphyrin production". Toxicology Letters. 161 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.09.005. PMID 16214298.

Further reading

[edit]- Fujita H, Kondo M, Taketani S, Nomura N, Furuyama K, Akagi R, Nagai T, Terajima M, Galbraith RA, Sassa S (October 1994). "Characterization and expression of cDNA encoding coproporphyrinogen oxidase from a patient with hereditary coproporphyria". Human Molecular Genetics. 3 (10): 1807–10. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.10.1807. PMID 7849704.

- Cacheux V, Martasek P, Fougerousse F, Delfau MH, Druart L, Tachdjian G, Grandchamp B (November 1994). "Localization of the human coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene to chromosome band 3q12". Human Genetics. 94 (5): 557–9. doi:10.1007/BF00211026. PMID 7959694. S2CID 11997203.

- Delfau-Larue MH, Martasek P, Grandchamp B (August 1994). "Coproporphyrinogen oxidase: gene organization and description of a mutation leading to exon 6 skipping". Human Molecular Genetics. 3 (8): 1325–30. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.8.1325. PMID 7987309.

- Martasek P, Nordmann Y, Grandchamp B (March 1994). "Homozygous hereditary coproporphyria caused by an arginine to tryptophane substitution in coproporphyrinogen oxidase and common intragenic polymorphisms". Human Molecular Genetics. 3 (3): 477–80. doi:10.1093/hmg/3.3.477. PMID 8012360.

- Maruyama K, Sugano S (January 1994). "Oligo-capping: a simple method to replace the cap structure of eukaryotic mRNAs with oligoribonucleotides". Gene. 138 (1–2): 171–4. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(94)90802-8. PMID 8125298.

- Martasek P, Camadro JM, Delfau-Larue MH, Dumas JB, Montagne JJ, de Verneuil H, Labbe P, Grandchamp B (April 1994). "Molecular cloning, sequencing, and functional expression of a cDNA encoding human coproporphyrinogen oxidase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (8): 3024–8. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.3024M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.8.3024. PMC 43507. PMID 8159699.

- Lamoril J, Deybach JC, Puy H, Grandchamp B, Nordmann Y (1997). "Three novel mutations in the coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene". Human Mutation. 9 (1): 78–80. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)9:1<78::AID-HUMU17>3.0.CO;2-M. PMID 8990017. S2CID 45889945.

- Daimon M, Gojyou E, Sugawara M, Yamatani K, Tominaga M, Sasaki H (February 1997). "A novel missense mutation in exon 4 of the human coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene in two patients with hereditary coproporphyria". Human Genetics. 99 (2): 199–201. doi:10.1007/s004390050338. PMID 9048920. S2CID 1813242.

- Schreiber WE, Zhang X, Senz J, Jamani A (1997). "Hereditary coproporphyria: exon screening by heteroduplex analysis detects three novel mutations in the coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene". Human Mutation. 10 (3): 196–200. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1997)10:3<196::AID-HUMU3>3.0.CO;2-H. PMID 9298818. S2CID 32065580.

- Suzuki Y, Yoshitomo-Nakagawa K, Maruyama K, Suyama A, Sugano S (October 1997). "Construction and characterization of a full length-enriched and a 5'-end-enriched cDNA library". Gene. 200 (1–2): 149–56. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00411-3. PMID 9373149.

- Lamoril J, Puy H, Gouya L, Rosipal R, Da Silva V, Grandchamp B, Foint T, Bader-Meunier B, Dommergues JP, Deybach JC, Nordmann Y (February 1998). "Neonatal hemolytic anemia due to inherited harderoporphyria: clinical characteristics and molecular basis". Blood. 91 (4): 1453–7. doi:10.1182/blood.V91.4.1453. PMID 9454777.

- Susa S, Daimon M, Kondo H, Kondo M, Yamatani K, Sasaki H (November 1998). "Identification of a novel mutation of the CPO gene in a Japanese hereditary coproporphyria family". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 80 (3): 204–6. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19981116)80:3<204::AID-AJMG4>3.0.CO;2-G. PMID 9843038.

- Rosipal R, Lamoril J, Puy H, Da Silva V, Gouya L, De Rooij FW, Te Velde K, Nordmann Y, Martàsek P, Deybach JC (1999). "Systematic analysis of coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene defects in hereditary coproporphyria and mutation update". Human Mutation. 13 (1): 44–53. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:1<44::AID-HUMU5>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 9888388. S2CID 2705450.

- Taketani S, Furukawa T, Furuyama K (March 2001). "Expression of coproporphyrinogen oxidase and synthesis of hemoglobin in human erythroleukemia K562 cells". European Journal of Biochemistry. 268 (6): 1705–11. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02045.x. PMID 11248690.

- Lamoril J, Puy H, Whatley SD, Martin C, Woolf JR, Da Silva V, Deybach JC, Elder GH (May 2001). "Characterization of mutations in the CPO gene in British patients demonstrates absence of genotype-phenotype correlation and identifies relationship between hereditary coproporphyria and harderoporphyria". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (5): 1130–8. doi:10.1086/320118. PMC 1226094. PMID 11309681.

- Elkon H, Don J, Melamed E, Ziv I, Shirvan A, Offen D (June 2002). "Mutant and wild-type alpha-synuclein interact with mitochondrial cytochrome C oxidase". Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 18 (3): 229–38. doi:10.1385/JMN:18:3:229. PMID 12059041. S2CID 42265181.

- Wiman A, Floderus Y, Harper P (2002). "Two novel mutations and coexistence of the 991C>T and the 1339C>T mutation on a single allele in the coproporphyrinogen oxidase gene in Swedish patients with hereditary coproporphyria". Journal of Human Genetics. 47 (8): 407–12. doi:10.1007/s100380200059. PMID 12181641.

External links

[edit]- Coproporphyrinogen+III+Oxidases at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)