Tradeston Flour Mills explosion

Drawing of the aftermath of the Tradeston Flour Mills explosion in the Illustrated London News on 20 July 1872 | |

| Date | 9 July 1872 |

|---|---|

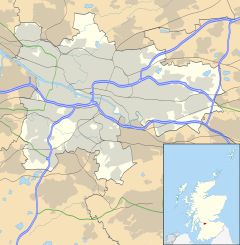

| Location | Tradeston, Glasgow, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°51′16″N 04°15′38″W / 55.85444°N 4.26056°W |

| Cause | dust explosion |

| Casualties | |

| 18 dead | |

| 16+ injured | |

On 9 July 1872 the Tradeston Flour Mills, in Glasgow, Scotland, exploded.[1][2] Eighteen people died,[3] and at least sixteen were injured.[1][4] An investigation suggested that the explosion was caused by the grain feed to a pair of millstones stopping, causing them to rub against each other, resulting in a spark or fire igniting the grain dust in the air. That fire was then drawn by a fan into an "exhaust box" designed to collect grain dust, which then ignited, causing a second explosion which destroyed the building. At the time, there were general concerns about similar incidents worldwide, so the incident and investigation were widely reported across the world.

Background

[edit]The mill was owned by Matthew Muir & Sons, had been in operation for thirty years, and consisted of a five-storey grain store on King Street (now Kingston Street), another grain store that occupied most of a four-storey building on Clyde Place, and a four-storey grain mill building between the two, with three boilers and an engine shed attached.[1] This occupied the majority of the block surrounded by Clyde Place, Commerce Street, King Street and Centre Streets, with Gorbals Free Church, the Bute Hotel, some shops and some dwelling houses taking up the rest of the block.[1]

Explosion

[edit]At 4 pm on 9 July, just as the day shift was about to finish, a large explosion blew out the front and back of the mill building.[1] Survivors of the explosion described a small initial explosion that filled the building with flour, and then a large explosion that blew out the walls.[5] The buildings were then engulfed in fire.[1] Employees of neighbouring businesses were also injured and killed in the explosion.[1] Six people were taken to the Royal Infirmary with serious injuries, while another ten with less serious injuries were sent home to recover.[1]

Firefighters were dispatched from all but one of the city's fire stations with firefighters from Bridgeton station being held in reserve in case of another fire. An off-duty firefighter from the Central Fire Brigade had actually witnessed the explosion and flames while working on a roof across the river. On arriving at the scene an immediate concern was preventing the fire from spreading to nearby buildings such as the riverside sheds or Bridge Street railway station. The windows of the station that faced onto Commerce Street had been shattered by the explosion, as well as parts of the glass roof, but firefighters were particularly concerned about the fire reaching the large spirit stores in the basement of the station. Ships like Anchor Line’s Sidonian were moved away from the quayside for fear of the fire spreading. After a few hours, the roof of the mill building collapsed and the remains of the wall facing onto Commerce Street collapsed into the street,[1] but by 11 pm the fire was considered under control.[5]

The following day, while the fire was contained but continued to burn within the ruins, work started to remove insecure pieces of the remaining buildings that faced onto the surrounding streets.[5] While engaged in this work, men discovered two bodies in a tenement at the corner of Clyde Place and Commerce Street;[5] one of them was Catherine Drennan, a young widowed mother of five.[5] Three of her children were not home at the time of the explosion, but while one girl survived the explosion and escaped the subsequent fire, a nine-month old daughter died.[5] Efforts were made to look for survivors and recover bodies throughout the day but only two bodies were recovered: Jane Mulholland from County Londonderry, Ireland, an employee of the Bute Hotel who had been retrieving clothes drying behind the hotel when the explosion occurred, and 14-year-old James Tanner from Donaghadee, Ireland, who had been working in the mill building.[5] During the day the site was visited by the city's Lord Provost Sir James Lumsden, Master of Works John Carrick, Dean of Guild Alexander Ewing and procurators fiscal John Lang and James Neil Hart.[5]

Work to recover bodies continued through until at least 8 August, with the final recovery being the body of 29-year-old Arthur Ferns, who had been employed in the mill.[6] This brought the total of deaths to eighteen (fourteen employees of the mill, three residents on Clyde Street and one employee of the Bute Hotel),[3] with at least sixteen injured.[1]

Victims

[edit]| Name | Age | Date recovered | Notes | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Bell Burrett | 12 | 5 August | Employed in the mill as a sweeper. | [7] |

| Arthur Ferns | 29 | 8 August | Employed in the mill. | [6] |

| Stewart Flacherty | 21 | 11 July | Employed in the mill as a labourer. | [3] |

| Christina Fraser | 38 | 10 July | A resident of the dwellings on Clyde Street. | [5] |

| Catherine Drennan (nee Graham) | 25 | 10 July | A resident of the dwellings on Clyde Street. | [3] |

| Helen Graham | 9 months | A resident of the dwellings on Clyde Street. She was reported as being with her mother Catherine Drennan at the time of the explosion. Her death is recorded as July 9 but her body was never recovered. | [3] | |

| Sarah Hamilton | 35 | 11 July | Employed in the mill. | [3] |

| William Imrie | 52 | 12 July | Employed in the mill. | [3] |

| James Laing | 20 | 11 July | Employed in the mill. | [8] |

| Thomas McCosh | 26 | 11 July | Employed in the mill. | [3] |

| Alexander McIntosh | 22 | 15 July | Employed in the mill. | [9] |

| Jane Mulholland | 30 | 10 July | Employed in the Bute Hotel. | [1] |

| John Robertson | 23 | 11 July | Employed in the mill. | [3] |

| John Rodger | 18 | Employed in the mill as an apprentice. His body was never recovered, and his death was registered August 31. | [1][10] | |

| John Smith | 23 | 16 July | Employed in the mill. | [11] |

| Betsy Tain | 26 | 13 July | Employed in the mill as a bag maker. | [12] |

| James Tanner | 15 | 10 July | Employed in the mill. | [5] |

| John Young | 24 | 16 July | Employed in the mill. | [11] |

Investigation

[edit]Professor of Civil Engineering and Mechanics at Glasgow University Macquorn Rankine and Dr. Stevenson Macadam, who lectured in Chemistry at the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, were asked by an insurance company to investigate the cause of the explosion.[13] They interviewed survivors, visited operating mills, and studied similar incidents, and published their report on 9 August.[14] They theorised that the explosion was caused by a spark or fire from a pair of millstones igniting the finely ground flour dust in the air.[13][14] Flour mills like the one at Tradeston had exhaust fans that drew flour dust from the mill stones into an "exhaust box" and from there into a stive room.[13][14] Rankine and Macadam stated that the grain feed to a pair of mill stones had stopped, while the stones kept turning, causing them to overheat.[13][14] They suggested that the stones started a fire that was drawn by the fan into the "exhaust box", which then exploded, distributing dust throughout the building; this dust then ignited, causing the second larger explosion reported by survivors.[13][14]

Their primary recommendation was that exhaust boxes and stive rooms should be housed outside mill buildings and designed to "be readily blown to pieces" so that, when similar fires happened, they would be drawn out of buildings themselves and the force of any explosion expended externally.[14] Their conclusions were reported around the world, from the Belfast News-Letter,[15] and London's The Pall Mall Gazette,[16] to Fort Wayne's Daily Sentinel[17] and The Brooklyn Daily Eagle.[18]

See also

[edit]- Great Mill Disaster – A similar dust explosion at a flour mill in Minneapolis in 1878

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Fearful Explosion and Great Fire in Tradeston - Great Loss of Life". The Glasgow Herald. 10 July 1872 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ John K. McDowall (1899). The People's History of Glasgow. Hay Nisbet & Co.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "The Explosion and Fire in Tradeston". The Glasgow Herald. 12 July 1872 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Price, David J.; Brown, Harold H. (1922). Dust Explosions. National Fire Protection Association, Boston, Mass.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Explosion and Fire in Commerce Street". The Glasgow Herald. 11 July 1872 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "The Catastrophe at Tradeston Mills - Remains of another body found". Glasgow Herald. 9 August 1872. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Tradeston Mill Catastrophe - Another Body Found". Glasgow Herald. 6 August 1872 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Tradeston Explosion". North British Daily Mail. 13 July 1872. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Recent Explosion and Fire in Tradeston". Glasgow Herald. 16 July 1872. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "John Rodger death certificate". 31 August 1872. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ a b "The Tradeston Catastrophe". Glasgow Herald. 17 July 1872. Retrieved 15 May 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Explosion and Fire in Tradeston". Glasgow Herald. 15 July 1872 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d e "Explosions in Flour Mills". Scientific American. 27 (14). 5 October 1872.

- ^ a b c d e f Cornelius Walford (1874). The Insurance Cyclopeadia. Charles and Edwin Layton, London.

- ^ "The Destruction of Tradeston Flour Mills, Glasgow". The Belfast News-Letter. 15 August 1872.

- ^ "Occasional Notes". The Pall Mall Gazette. 22 August 1872.

- ^ "Will Flour Explode? - The Question Considered from a Scientific Stand-Point by a Noted Scotch Chemist". Daily Sentinel. 15 January 1873.

- ^ "Miscellaneous Items". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 17 December 1873.

- 1870s in Glasgow

- 19th-century fires in the United Kingdom

- 1872 disasters in the United Kingdom

- 1872 fires

- 1872 in Scotland

- Building and structure fires in Scotland

- Building and structure collapses caused by fire

- Building and structure collapses in the United Kingdom

- Commercial building fires

- Disasters in Glasgow

- Dust explosions

- Explosions in 1872

- Explosions in Scotland

- Fire and rescue in Scotland

- Food processing disasters

- Food processing industry in the United Kingdom

- Gorbals

- Industrial fires and explosions in the United Kingdom