FOXP3

FOXP3(forkhead box P3)またはScurfinは、免疫応答に関与するタンパク質である[5]。FOXP3はFOXタンパク質ファミリーのメンバーであり、制御性T細胞(Treg)の発生と機能の調節経路のマスターレギュレーターとして機能する[6][7][8]。一般的に、制御性T細胞は免疫応答を抑える役割を果たす。がんでは制御性T細胞の過剰な活性によってがん細胞が免疫系による破壊を免れている場合があり、また自己免疫疾患では制御性T細胞の活性の欠乏によって他の自己免疫細胞による自組織への攻撃が行われるようになっている場合がある[9][10]。

その正確な制御機構は十分には解明されていないものの、FOXタンパク質群は類似したDNA結合特性によって転写制御を行っていると考えられている。制御性T細胞のモデル系では、FOXP3は制御性T細胞の機能に関与する遺伝子群のプロモーターに結合し、またT細胞受容体刺激後に重要な遺伝子の転写を阻害している可能性がある[11]。

遺伝子

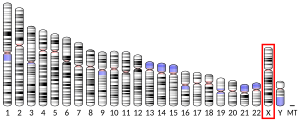

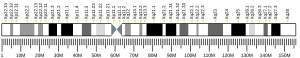

[編集]FOXP3遺伝子は11個のエクソンから構成される。マウスとヒトの遺伝子でコーディング領域のエクソン-イントロン境界は同一である。FOXP3遺伝子はX染色体の短腕(Xp11.23)に位置する[5][12]。

生理

[編集]FOXP3は内在性Treg(nTreg)や誘導性Treg(iTregまたはaTreg)の特異的マーカーであり、またこれらの細胞はCD25、CD45RBなどのより特異性の低いマーカーによっても同定される[6][7][8]。動物研究では、Foxp3を発現するTregは免疫寛容、特に自己寛容に重要であることが示されている[13]。

動物研究では、糖尿病、多発性硬化症、気管支喘息、炎症性腸疾患、甲状腺炎、腎臓病モデルにおいて、Foxp3陽性T細胞の誘導または投与によって自己免疫疾患の重症度が顕著に低減されることが示されている[14]。ヒトにおいても、Tregを用いた移植片対宿主病の治療の有効性が示されている[15][16]。

一方、T細胞は当初考えられていたよりも可塑性が高いことが示されている[17][18][19]。このことは治療におけるTregの利用がリスクを伴う可能性を意味しており、一例として宿主へ投与されたTregは炎症促進性のTh17細胞へ変化する可能性がある[17]。Th17細胞が産生される環境はiTregと類似しており[17]、Th17細胞はTGF-βとIL-6(またはIL-21)の影響下で産生されるのに対し、iTregはTGF-βのみの影響で産生される。

FOXP3はTreg系列のマスターレギュレーターとして同定されており、ヒストン標識に依存してアクチベーターとしてもリプレッサーとしても機能する[20]。FOXP3遺伝子の発現はナイーブT細胞からTregへの変換をもたらすことが知られており、Tregはin vivoやin vitroで免疫抑制能を有する。このことは、FOXP3が免疫抑制を媒介する因子の発現を調節していることを示唆しており、FOXP3の標的の同定がTregによる免疫抑制の理解に重要となる可能性を示している[20]。

病態生理

[編集]Tregの数の変化、特にFOXP3を発現している細胞の数の変化は、多くの疾患でみられる。一例として、腫瘍を有する患者ではFOXP3陽性T細胞が局所的に相対的に過剰に存在し、がん細胞形成を抑制する能力が阻害されている[21]。逆に、全身性エリテマトーデスなどの自己免疫疾患の患者では、FOXP3陽性細胞が相対的に機能不全を起こしている[22]。また、IPEX症候群ではFOXP3遺伝子に変異が生じている[23][24]。IPEX症候群の患者の多くでは、DNA結合を担うフォークヘッドドメイン領域に変異が生じている[25]。

マウスでは、Foxp3の変異(フォークヘッドドメインの喪失が引き起こされるフレームシフト変異)によって"Scurfy"と呼ばれるX連鎖劣性遺伝変異体マウスとなり、ヘミ接合型オスマウスは出生後16から25日で致死となる[5]。この変異体マウスでは、CD4+T細胞の過剰増殖、広範囲にわたる多臓器浸潤、多数のサイトカインの上昇が生じる。この表現型は、CTLA-4やTGF-βの発現を欠くマウスや、IPEX症候群のものとも類似している[5]。Foxp3遺伝子を過剰発現するマウスでは、T細胞数の減少が観察される。残りのT細胞も増殖能や細胞溶解応答、IL-2産生が乏しいが、胸腺の発生は見かけ上正常である。組織学的解析では、末梢リンパ器官、特にリンパ節で正常な細胞数がみられない[26]。

がんにおける役割

[編集]FOXP3の多型(rs3761548)は、Tregの活性や、IL-10、IL-35、TGF-βといった免疫調節サイトカインの分泌に影響を及ぼすことで、胃がんなどの発生に寄与している可能性がある[27]。P60と呼ばれる15-merの合成ペプチドは細胞内へ移行してFOXP3に結合し、FOXP3の核移行を妨げることが示されている。その結果、FOXP3はNF-κBやNFATといった転写因子を抑制することができなくなる。こうしたFOXP3阻害ペプチドによってTregの機能を阻害することで、抗腫瘍免疫療法の効果を高めることができる可能性がある[28]。

自己免疫

[編集]FOXP3調節経路の変異や破綻は、自己免疫性甲状腺炎や1型糖尿病といった器官特異的自己免疫疾患につながる場合がある[29]。こうした変異は胸腺内で発生する胸腺細胞に影響を及ぼす。胸腺細胞はその分化の際に、FOXP3によって調節を受けて成熟型Tregへ形質転換する[29]。全身性エリテマトーデスの患者の一部にはこの過程に影響を及ぼすFOXP3変異がみられるが明らかにされており、胸腺内で適切なTreg細胞の発生が生じなくなっている[29]。こうした機能不全型Treg細胞は転写因子による効果的な調節を受けず、健康な細胞を攻撃することで器官特異的な自己免疫疾患につながる。また、FOXP3は炎症抑制を媒介する分子の発現調節を介して、自己免疫系の恒常性を維持ししている。一例として、FOXP3はCD39の発現を誘導し[30]、細胞外のATPの分解促進をもたらす[31]。CD39は炎症性分子であるATPを抗炎症分子であるアデノシンへ分解するカスケードの律速段階となる酵素であり、さまざまな細胞集団で免疫抑制を調節する[31]。

出典

[編集]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000049768 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000039521 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:

- ^ a b c d “Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse”. Nature Genetics 27 (1): 68–73. (January 2001). doi:10.1038/83784. PMID 11138001.

- ^ a b “Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3”. Science 299 (5609): 1057–61. (February 2003). Bibcode: 2003Sci...299.1057H. doi:10.1126/science.1079490. PMID 12522256.

- ^ a b “Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells”. Nature Immunology 4 (4): 330–6. (April 2003). doi:10.1038/ni904. PMID 12612578.

- ^ a b “Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3”. Immunity 22 (3): 329–41. (March 2005). doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. PMID 15780990.

- ^ “Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function”. Annual Review of Immunology 30 (January): 531–64. (January 2012). doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. PMC 6066374. PMID 22224781.

- ^ “The regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory CD4(+)CD25(+)T cells: multiple pathways on the road”. Journal of Cellular Physiology 211 (3): 590–7. (June 2007). doi:10.1002/jcp.21001. PMID 17311282.

- ^ “Foxp3 occupancy and regulation of key target genes during T-cell stimulation”. Nature 445 (7130): 931–5. (February 2007). Bibcode: 2007Natur.445..931M. doi:10.1038/nature05478. PMC 3008159. PMID 17237765.

- ^ “X-Linked syndrome of polyendocrinopathy, immune dysfunction, and diarrhea maps to Xp11.23-Xq13.3”. American Journal of Human Genetics 66 (2): 461–8. (February 2000). doi:10.1086/302761. PMC 1288099. PMID 10677306.

- ^ “Tolerance induced by thymic epithelial grafts in birds”. Science 237 (4818): 1032–5. (August 1987). Bibcode: 1987Sci...237.1032O. doi:10.1126/science.3616623. PMID 3616623.

- ^ “Regulatory T cells in experimental autoimmune disease”. Springer Seminars in Immunopathology 28 (1): 3–16. (August 2006). doi:10.1007/s00281-006-0021-8. PMID 16838180.

- ^ “Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics”. Blood 117 (3): 1061–70. (January 2011). doi:10.1182/blood-2010-07-293795. PMC 3035067. PMID 20952687.

- ^ “Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation”. Blood 117 (14): 3921–8. (April 2011). doi:10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. PMID 21292771.

- ^ a b c “Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation”. Immunity 30 (5): 646–55. (May 2009). doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001. PMID 19464987.

- ^ “The functional plasticity of T cell subsets”. Nature Reviews. Immunology 9 (11): 811–6. (November 2009). doi:10.1038/nri2654. PMC 3075537. PMID 19809471.

- ^ “Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances”. Nature Immunology 11 (8): 674–80. (August 2010). doi:10.1038/ni.1899. PMC 3249647. PMID 20644573.

- ^ a b “Regulatory T cells and Foxp3” (英語). Immunological Reviews 241 (1): 260–8. (May 2011). doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01018.x. PMC 3077798. PMID 21488902.

- ^ “Regulatory T cells in cancer”. Blood 108 (3): 804–11. (August 2006). doi:10.1182/blood-2006-02-002774. PMID 16861339.

- ^ “Regulatory T cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus”. Journal of Autoimmunity 27 (2): 110–8. (September 2006). doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2006.06.005. PMID 16890406.

- ^ “The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3”. Nature Genetics 27 (1): 20–1. (January 2001). doi:10.1038/83713. PMID 11137993.

- ^ “Regulatory T Cells in Cancer”. Annual Review of Cancer Biology 4 (1): 459–477. (2020-03-09). doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033428.

- ^ “IPEX as a result of mutations in FOXP3”. Clinical & Developmental Immunology 2007: 89017. (2007). doi:10.1155/2007/89017. PMC 2248278. PMID 18317533.

- ^ Khattri, R.; Kasprowicz, D.; Cox, T.; Mortrud, M.; Appleby, M. W.; Brunkow, M. E.; Ziegler, S. F.; Ramsdell, F. (2001-12-01). “The amount of scurfin protein determines peripheral T cell number and responsiveness”. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 167 (11): 6312–6320. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6312. ISSN 0022-1767. PMID 11714795.

- ^ “Association of Foxp3 rs3761548 polymorphism with cytokines concentration in gastric adenocarcinoma patients”. Cytokine 138: 155351. (February 2021). doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2020.155351. ISSN 1043-4666. PMID 33127257.

- ^ “A peptide inhibitor of FOXP3 impairs regulatory T cell activity and improves vaccine efficacy in mice” (英語). Journal of Immunology 185 (9): 5150–9. (November 2010). doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1001114. PMID 20870946.

- ^ a b c “Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3” (英語). Science 299 (5609): 1057–61. (February 2003). Bibcode: 2003Sci...299.1057H. doi:10.1126/science.1079490. PMID 12522256.

- ^ Borsellino, Giovanna; Kleinewietfeld, Markus; Di Mitri, Diletta; Sternjak, Alexander; Diamantini, Adamo; Giometto, Raffaella; Höpner, Sabine; Centonze, Diego et al. (2007-08-15). “Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression”. Blood 110 (4): 1225–1232. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 17449799.

- ^ a b “Overexpression of CD39 in hepatocellular carcinoma is an independent indicator of poor outcome after radical resection”. Medicine 95 (40): e4989. (October 2016). doi:10.1097/md.0000000000004989. PMC 5059057. PMID 27749555.

関連文献

[編集]- “FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT”. Cell 126 (2): 375–87. (July 2006). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. PMID 16873067.

- “The role of the FOXP3 transcription factor in the immune regulation of allergic asthma”. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports 5 (5): 356–61. (September 2005). doi:10.1007/s11882-005-0006-z. PMID 16091206.

- “FOXP3 ensembles in T-cell regulation”. Immunological Reviews 212: 99–113. (August 2006). doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00405.x. PMID 16903909.

- “FOXP3: not just for regulatory T cells anymore”. European Journal of Immunology 37 (1): 21–3. (January 2007). doi:10.1002/eji.200636929. PMID 17183612.

- “Role of regulatory T cells and FOXP3 in human diseases”. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 120 (2): 227–35; quiz 236–7. (August 2007). doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.06.023. PMID 17666212.

- “Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked inheritance: model for autoaggression”. Immune-Mediated Diseases. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 601. (2007). pp. 27–36. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_3. ISBN 978-0-387-72004-3. PMID 17712989

- “Understanding FOXP3: progress towards achieving transplantation tolerance”. Transplantation 84 (4): 459–61. (August 2007). doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000275424.52998.ad. PMID 17713426.

- “DNA cloning using in vitro site-specific recombination”. Genome Research 10 (11): 1788–95. (November 2000). doi:10.1101/gr.143000. PMC 310948. PMID 11076863.

- “JM2, encoding a fork head-related protein, is mutated in X-linked autoimmunity-allergic disregulation syndrome”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 106 (12): R75–81. (December 2000). doi:10.1172/JCI11679. PMC 387260. PMID 11120765.

- “X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy”. Nature Genetics 27 (1): 18–20. (January 2001). doi:10.1038/83707. PMID 11137992.

- “Scurfin (FOXP3) acts as a repressor of transcription and regulates T cell activation”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (40): 37672–9. (October 2001). doi:10.1074/jbc.M104521200. PMID 11483607.

- “Novel mutations of FOXP3 in two Japanese patients with immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X linked syndrome (IPEX)”. Journal of Medical Genetics 38 (12): 874–6. (December 2001). doi:10.1136/jmg.38.12.874. PMC 1734795. PMID 11768393.

- “X-chromosome inactivation analysis in a female carrier of FOXP3 mutation”. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 130 (1): 127–30. (October 2002). doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01940.x. PMC 1906506. PMID 12296863.

- “A functional polymorphism in the promoter/enhancer region of the FOXP3/Scurfin gene associated with type 1 diabetes”. Immunogenetics 55 (3): 149–56. (June 2003). doi:10.1007/s00251-003-0559-8. PMID 12750858.

- “Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25- T cells”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 112 (9): 1437–43. (November 2003). doi:10.1172/JCI19441. PMC 228469. PMID 14597769.

- “Mutational analysis of the FOXP3 gene and evidence for genetic heterogeneity in the immunodysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy syndrome”. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 88 (12): 6034–9. (December 2003). doi:10.1210/jc.2003-031080. PMID 14671208.